There are 42 articles in the Convention of the Rights of the Child that are predominately centred around the idea that parents and governments are responsible for the physical and emotional safety of children. The convention states that children have a right to feel safe from any type of harm. As parents, mentors, teachers, youth workers or anyone else who is in a position of authority, it is our responsibility to uphold this right. Unfortunately, children are still being harmed.

It’s hard to believe that in a country like Australia, there is still a frightening amount of children experiencing child abuse each year. In Australia between 2016–17, 168,352 children received child protection services, a rate of 30.8 per 1,000 children aged 0–17. Of children receiving child protection services in 2016–17:

• 119,173 were the subject of an investigation (21.8 per 1,000)

• 64,145 were on a care and protection order (11.7 per 1,000)

• 57,221 were in out-of-home care (10.5 per 1,000).

Specifically in Victoria, 11,077 children were the subject of substantiated investigations, and 11,111 were the subject of investigations that were not substantiated.

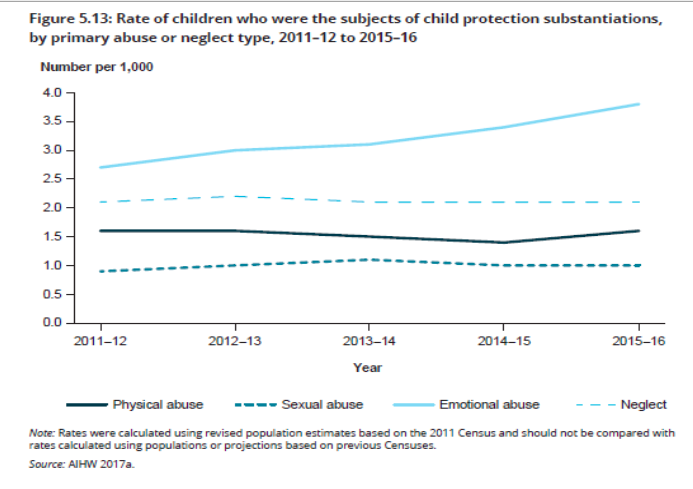

The chart below indicates that rates of child abuse have either remained the same or increased over a five year period between 2011 and 2016. Of particular note are the rates of child emotional abuse, which are gradually increasing each year.

Why the increase in rates of emotional abuse?

The increase of rates of emotional abuse could be attributed to the fact that emotional abuse of children became more well recognised after the Royal Commission into Family Violence, and therefore more heavily reported on. Whereas historically, emotional abuse was not always as obvious and was often difficult to identify (compared to physical and sexual abuse).

The Royal Commission into Family Violence was conducted from 2015-2016 and its’ aim was to prevent family violence, improve early intervention, support victims, make perpetrators accountable, better coordinate community and government responses as well as evaluate and measure strategies, frameworks, policies, programs and services. It was established following a series of family violence related deaths in Victoria, most notably – 11 year old Luke Batty – who was killed by his father in February 2014 following a long history of violence perpetrated against his mother, Rosie Batty.

According to the Royal Commission into Family Violence;

The Royal Commission highlighted this issue within the family violence service system and developed recommendations for change. This could explain the increased rates of reported emotional abuse from 2014-2016.

So how do we prevent child abuse? This is a very loaded question and I can’t expect any one person to have the answer. For this reason I’ve asked some professionals within the Ultimate Youth Worker community to share their thoughts on this important topic. They’ve shared their experiences and wisdom from several different perspectives.

The child protection perspective:

- What do you see as the main factors in the prevention of child abuse? How can we help parents and families to avoid inter-generational abuse?

“When thinking about preventative approaches to child abuse I think it’s constructive to recognise the use of primary, secondary and tertiary services as the platform for better ensuring the safety and well-being of children and reducing the risk of inter-generational abuse and neglect.

All interventions need to be grounded in an understanding of the complex and compounding issues associated with abuse and neglect including (but not limited to); AOD, family violence and mental health factors. The focus should be on the delivery of psycho-education to increase community and public awareness around risk and protective factors for children, their development and healthy family dynamics.

It should also involve the development of intensive programs, strategies and interventions that target already vulnerable families giving them maximum opportunity to break the cycle of violence. Furthermore, these programs must be culturally specific, relatable and engage therapeutic supports and rehabilitation programs to reduce the risk of future harm to families already challenged by the experience of violence.

In some instances, this needs to be balanced with the use of mental health interventions, legal prosecutions and criminal proceedings where necessary and appropriate. This is in order to reduce risk of recidivism and ensure greater responsibility and accountability for those perpetrating harm.”

(Lani, social worker)

The young person’s perspective:

- What are some of the most common behavioural traits that you see in young people that have experienced abuse or family violence?

“Not trusting adults and going through an extended phase of “testing” when they meet a new adult. A young person might put on different masks at different stages of the testing phase. Initially, they might be very nice, then become very quiet and reserved. Once they feel that you are safe to be around they can often escalate, testing you with all different kinds of challenging behaviours.One of the most challenging things young people who have experienced violence and abuse face is low self worth and self esteem. They often don’t believe they can be good at anything, so you need to find little things that demonstrate their strengths and reinforce these things.

It’s important to support these young people by consistently being there with positive reinforcement and a protective environment.”(Nadav, youth worker)

The family/parent perspective:

- What’s your experience of working with families where abuse has occurred?

“Most of my contact is with the mother, some of whom are not Australian citizens. These women hold tremendous strength and resilience where their visa status is unknown, access to government income is little or non existent, access to affordable housing is not an option and their rights to their child/ren are questioned by child protection and challenged by the family courts. In some cases, where returning to their country of origin will place the family in danger from relatives, they are overlooked by our family violence refuge and housing systems.

In the face of so much adversity, it is these women that continue to prioritise their child/ren’s safety and continue to parent their children as best they can with little to no resources.

Many women we work with, both CALD and Australian born often don’t understand that they have been experiencing family violence. A large part of our work is assessing immediate safety and risk. We work from a client centred, trauma informed and strengths based framework.

However there is an enormous amount of work (educative model) to explain and unpack their experiences of family violence. We start to introduce these concepts to the women. As we are a crisis service, we hand this over along with the case plans to the refuge for the ongoing family violence case management of the women and children. From there they are linked into group work and victim-survivor advocacy.

It is quite shocking sometimes when speaking to women where there is no understanding that the violence is abuse and a criminal act. It’s about providing information and options and allowing them the space to reflect on their experiences and shift their understanding.”

(Cindy, social worker)

The child’s perspective:

- How can we help children in the prevention of child abuse?

– Create a safe space within schools and support services that children can feel comfortable within if they need to disclose abuse.

– Encouraging children to speak out if something has happened to them.

– Educating school staff and other professionals (early child care workers, social workers, GPs, nurses, psychologists) to look out for signs of harm/abuse and train them how to navigate a disclosure of abuse.

– Making books available in your service or classroom that promote body safety. Such as books by Jayneen Sanders.

– Having story books available in your service or classroom that discuss family violence.

– Therapeutic work with children and families.

(Sammy, social worker)

At Ultimate Youth Worker, we are committed to being a child safe organisation that recognises, respects and promotes children’s rights. Read more about our commitment in our blog. Thank you for taking the time to visit us today, make sure you visit our social media pages and join in the conversation.

Further Reading: