Tag Archives: youth work sector

What will youth work look like in 2013? The finale.

Its been a month and a half in the making but we are finally there. The finale of our series looking at the next twelve months or more in youth work. We have had blogger’s and professor’s of youth work from one end of the globe to the other. We heard from Shae and Stephen from youthworkinit.com, Sam Ross from teenagewhisperer.com, Professor Dana Fusco from CUNY and Professor Howard Sercombe from the University of Strathclyde. Each had their own perspectives on the current and future trends in youth work. Each brought a different perspective on what forces were pushing and pulling youth work. Each one had a particular pearl of wisdom for us. Today’s post is a wrap up of these posts with a focus on the similarities between them all. We will also give our view of the year ahead.

Wrap up

Our amazing guests spoke about a number of areas in which youth work will develop over the coming year. They spoke about youth worker education, technology, the economic situation and the need to be holistic in our practice.

Youth Worker Education

Dana Fusco spoke of the changes developing in youth work education world wide. In the US there has been a 900% increase over the past four years in youth development courses offered by higher education facilities. In the UK and Australia These courses are in decline. Dana laments the decline in youth work education, “In 2013, it is hard to predict where those who want to study youth work and youth studies in these countries will go. If they go into existing, related disciplines, e.g., social work, then youth work will too likely become case management; if they go into education, then youth work will become para-teaching“.

Howard Sercombe also laments the current education setting for youth worker’s. From developing a cozy little home for ourselves throughout the sixties and seventies to becoming a mainstream course in the nineties we sold our soul to the devil of higher education. Like all good corporate conglomerates the universities shafted us. Taking a subject area steeped in the tradition of practice wisdom and narrative and turning it into a McDonaldised cookie-cutter model of research-based best-practice. However true to our history we steered away from research which ultimately is leading to our higher education downfall. Conversely, Howard states, “For the first time, I can run a course for youth workers using a selection of books on youth work written by youth workers“.

Technology

In her response to the question Sam Ross states that she always thinks of the new technology on the horizon. Sam speaks of the massive uptake of mobile and smart phones by young people. She shows the statistics of American young people’s use of their phone and how much of their attention it takes…Are you on social networking sites? They are! Sam speaks of the need for youth workers to use this love of mobile technology to keep the attention of young people focused on what we want them focused on.

However Sam also implores us, “So while 2013 may be technologically more advanced and our ways of connecting and engaging may expand we shouldn’t forget that good youth work was the same in the past as it is today and will be tomorrow“. Its all about the relationship.

The economic situation

There is not a person alive today that can’t attest to the effects of the global financial crisis on the hip pocket. Everything seems to cost more today than it did yesterday. Even in countries like Australia which have had some reprieve from the tidal forces of the economic collapse the financial situation is difficult. As Howard put it “Austerity measures have required significant cutbacks in local funding and this has carried through, often disproportionately, to youth work services“. But we are not the only ones feeling the pinch. Our young people are finding employment harder to gain, University fees have shot through the roof and the general cost of business has increased significantly.

For youth workers this means difficulties at every turn. Shae and Stephen state, “Over the last 25 years, the cost of university education in the US has more than tripled, which has resulted in 1 in 11 people defaulting on their student loan repayments within two years of making payments“. Many of our guests stated that this cost was prohibitive and that if you are one of those who are entering a university to study youth work then you are likely to pay through the nose and then struggle to pay it back.

If you rely on government funding or philanthropic support to run your organisation you may be short on funds for a while. Many governments are finding their budgets significantly in the red. Many philanthropic organisations have seen their investments dip over the past few years as well and are giving out less to allow for their continuation. Its not happening everywhere yet but as Howard said, “2013 may well be the year when the expected decimation actually happens“.

The need to be holistic in our practice.

Gone are the days where youth work happens in a silo. On any given day we are expected to hold a number of roles. Sam points out that our ability to build relationships with young people is core to our work and that this foundation is what we build on in our context. Shae and Stephen point out that young people do not live in silos but have lives with intersecting and overlapping parts. Work on one without the other areas being addressed is ineffective.

Dana states, “In the United States, youth work is not a unified or singular practice; rather, it has been described, and still is, a family of practices“. Its not just the states, its world wide. We work from the same base but in different contexts. Our young people need us to have an understanding of more than how to run a good game. As copious as the needs of our young people are, the knowledge of a youth worker must equal… at least enough to refer to other professionals.

What will 2013 look like???

At Ultimate Youth Worker we have loved the guest posts over the last month and a half and have been pouring over them and a bunch of other research and have come to many of the same conclusions. Technology is going to be more important this year than ever before. 12 months on from the death of Steve jobs saw the smart phone war at its highest. Exponential growth in mobile, web and personal technology has meant that the ability to communicate or gain information has never been more accessible. Youth workers need to become more tech savvy just to survive. New web applications, social media and even the ubiquitous email are more important than ever to our relationship building. As youth workers we believe there will be a shift to online training, both formal and informal. Blogs, webinars, podcasts, university course and professional development groups are all starting to toy with developing a solid presence on the web. With the hardware never more than arms length from most young people and youth workers we need to be there.

Youth work education will need to adapt. Aside from becoming more tech enabled we need to gain more breadth and more depth in our education. Young people are changing so fast that we need to keep up with the trends. We hang our shingle on our ability to develop relationships with young people. Good. But we need to develop this skill set. We are a relatively emergent human services field and as such need to develop our purpose, values and critical approach. This is depth. We also need to gain an understanding of where we fit in the multidisciplinary field that young people now frequent. We need an understanding of who and what our colleagues in other field bring to the table. We need to understand their language, their approach and their skill sets. It is the only way we will be able to speak into their work and intervene for our young peoples best.

Money has never been more important and less relevant. The affect of the financial crisis is all around us and will continue to mess with us for years to come in ways we can’t even imagine yet. IT DOESN’T MATTER. The most effective tools in our toolkit are FREE or really cheap. Building relationships takes time. A facebook page can be accessed by free wi-fi at McDonald’s. A mobile phone plan is cheaper than ever. The tools to build relationships are time, energy and interest. Most youth workers have that in trumps. But that means we need to have them around. Youth workers need to feed their families too. With lay-offs happening throughout the sector worldwide there is fear of being cut. Like Howard says, its happened before. The cycle will return. Be the best you can be with what you’ve got and you will be one of the last to get chopped.

Be more!!! Be holistic. What do you do when you have that relationship? We believe youth workers need to see young people as whole people in their context. We need a biopsychoscialspiritual focus. We need to understand the person, their context and their pathways out of their situation. We need to support our young people in every way we can. We also need to look after ourselves. As the stress builds and we are asked to become more and do more we need to have the reserves to keep going.

We also agree with Dana and Howard, Now is the time for an international presence developing the practice of youth work. We are seeing great international youth work research, texts, blogs, conferences etc coming to the fore. We need to build on this.

2013 holds possibilities and risks. We have tried to play it safe for the last decade or more and have seen the rug being pulled out from under us. No more politically light weight youth work. We must band together and do it differently or we will see the death knell of what we hold dear… relationally based critical youth work.

What will youth work look like in 2013?

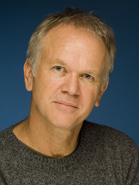

It is with great pleasure and a sad heart that we come to our final guest post in this series. We have heard from a number of truly inspirational and well qualified youth work professionals as to what they believe youth work will look like in 2013. Over the last three weeks we have had Shae and Stephen from youthworkinit.com, Professor Dana Fusco of CUNY and author of “Advancing Youth Work: current trends, critical questions” and fellow blogger and youth work professional Sam Ross the teenage whisperer. This week we have the distinct pleasure to hear from Professor Howard Sercombe of the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland.

Howard has researched extensively in the area of youth studies, including studies of the future of youth, young people and public space, and community development with young people. He is interested in how we think about young people, and is currently working with colleagues from neurophysiology and developmental psychology on the implications of the brain architecture research on our understanding of young people. Professor Sercombe has had a major role in the development of youth work as a profession. His scholarship around this area includes writing the Australian Code of Ethics for Youth Work which has been adopted or adapted in three Australian States and the Australian Capital Territory and is under consideration nationally. He also wrote the Code of Ethics for the profession in Scotland. He has lectured extensively across the UK, Australia, New Zealand and Zambia on professional ethics and professionalisation, and his book Youth Work Ethics (Sage, 2010) is a milestone in the field. He is currently developing approaches to research methodology that take seriously the ethical commitment to justice and development.

So Howard what’s your take on the future of youth work?

Realities, as always, are contradictory. Mixed. From the perspective of the UK, things look grim. The fiscal crisis has hit the traditional funding sources of youth work hard. For the last fifty years, local government has had a statutory responsibility to make provision for youth work, though local authorities have had a lot of latitude about how, and to some extent if, they carry this out. Austerity measures have required significant cutbacks in local funding and this has carried through, often disproportionately, to youth work services.

But this picture is mixed. Some authorities have actually increased funding to youth work, in recognition of the impact of the recession on young people. Others have cut provision completely. As a generalisation, however, cutbacks have been widespread and often deep. In Scotland, where I live, cutbacks have been worrying but not catastrophic, at least not everywhere. 2013 may well be the year when the expected decimation actually happens. The real concern is that this fiscal crisis is not a temporary adjustment, and future cutbacks look like coming on top of the existing ones. Even when the recession is over, we face the fiscal time bomb of an ageing population. Some are proclaiming the death of youth work as we know it in the UK.

Some of us have been here before, however. Political economists in the 1970s talked about the contradiction between accumulation and legitimation: the need for the State to continue to guarantee profit and private accumulation, while reassuring the general population that the system was still working in their interests. It is typical in the early phase of a fiscal crisis for the State to pull back from areas of expenditure it sees as optional, in order to support capital in its restructuring and rebalancing. Youth work is politically lightweight, so we tend to fall into that category. Then, two years in, the entirely predictable spectre of youth unemployment starts to raise its head. That is followed by a crime wave, or a moral panic about one, and there is a panic reinvestment in youth work to deal with it. I’m expecting the same pattern. The London riots came too early in the process to have that effect, and was able to be dismissed by the political class in terms of a cultural moral deficit and individual criminality. A repeat may not be as easily dismissed.

But all recessions are different, and this one different to most. Most come on the back of an economic boom, leaving the State with at least some financial capacity to manage the recession. The need to bail out the banks right at the beginning of the crisis meant that affected governments hit the recession already broke. That means that the capacity of the State to reinvest is limited. Youth work will continue to be done, but we might see a significant return to voluntary labour to get the hours in. In fact we already are!

Youth work education is in a difficult place as well. Youth work found a place in professional education in the universities from the 1960s, with real growth in the 80s and 90s. In the last decade, however, the situation has shifted. The focus on research has diminished the respect for practice wisdom in professional education, and youth work (along with other professional areas like teaching) has not kept up with the research agenda. Corporatisation in the university sector has meant more aggressive pursuit of objectives that promote the university as a corporation rather than the objectives of public service: and that means either high status or high earning activities. Youth work is not a natural contender for either. The poorly thought out introduction of fees in England has meant that training for low-earning professions like youth work are charged at the same rate as high earning professions like law, with a significant impact on demand. The number of universities who have decided to close youth work courses is still a trickle rather than a flood, but some of those courses (including my own) were strategic and long-standing.

But that isn’t the whole story.

Beyond the question of funding and institutional support, there is a growing level of maturity in the youth work profession in the current environment, and a clearer assertion of identity. Paradoxically, even while the funding base contracts, for example, the Scottish Government continues to insist that community learning and development, which embraces youth work, sits at the centre of its anti-poverty and inclusion strategies. The House of Commons Education Committee inquiry into youth services also provided a ringing endorsement of youth work, though noted the lack of a credible evidence base for its effectiveness. The Irish and South African government has a very active division working on the professionalisation of youth work, government does too. Several governments have established youth work in law, with more heading in that direction.

The consolidation of youth work practice through codes of ethics and other core constitutive documents has been progressing across the globe in the last decade. Professional organisations for youth workers are springing up everywhere. Globalisation has meant an international community of youth workers, with more international conferences, policy conversations, research and collaboration. There are more books published on youth work, by major commercial publishers, than ever before. Routledge has just commissioned a new series of books on youth work practice. Sage has taken over the locally-published Learning Matters series. For the first time, I can run a course for youth workers using a selection of books on youth work written by youth workers. This is mirrored in journal and on-line publication as well. Youth work is moving beyond the parochial, and is recognising its common core beyond local expressions of it. It is becoming an international profession.

And there is a bigger picture. The modern category of youth is an artefact of modernisation itself. At other times and in other places, young people were much more integrated intergenerationally, and had a clear role. Modern industry required fewer workers, and more educated, literate and disciplined workers. What happened was the quarantining of people by age into educational institutions, their isolation from the relations of production and from contact with adult social institutions and the subsequent emergence of a (now global) youth culture. This creates a youth population which is significantly, but incompletely contained by the school and other educational institutions. There are also key developmental processes around people becoming autonomous and self-directed which total institutions like the school are not good at facilitating. Youth work exists in all modern societies, under whatever guise and however resourced, because it is socially necessary. It emerged during the Industrial Revolution, and has a continuous presence ever since.

The industrialisation and modernisation process is spreading apace throughout the world: particularly in the new economic powerhouses: the ‘BRICS’ countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa). All of them have huge, underemployed youth populations, and are very aware of the political time bomb that involves. In the next decade, all of them will need to make decisions about youth policy, and divert resources towards young people. How youth work positions itself within that process remains to be seen.

Professor Sercombe is an experienced youth work practitioner, trainer, consultant, analyst, media commentator and researcher in the youth studies area. He has primary experience in street-level youth work with homeless and street-present young people as well as a developed academic profile with expertise ranging from social policy analysis to adolescent development to professional ethics. He has worked in urban settings as well as remote outback towns, with Aboriginal and mainstream young people, and across a range of methodologies.

Notwithstanding his current position in the university, Howard sees himself as first and foremost a youth worker, as he has for the last thirty years. His current work is focuses on how youth workers can understand their role and their work, how conceptions of young people shape their practice, on the peculiar ethics of youth work as a profession, and how truth is created and translated between policy, research and practice. He is also working on the implications of the adolescent brain research for our understanding of young people and the practice of youth work. He rides a Yamaha 1200 VMax motorcycle with a sidecar, is married to broadcaster Helen Wolfenden, and has three sons.

What will youth work look like in 2013?

Today I am stoked to continue our series with a guest post from one of the worlds most well known youth work professors. In this series we have heard from Shae and Stephen Pepper from youthworkinit.com and will continue to hear from some of the leading minds in youth work from throughout the world culminating in early 2013.

Today’s Guest Post is written by one of New York’s finest, Professor Dana Fusco. In over 20 years as a lecturer in youth work she has shaped the argument for youth services in the United States encompassing areas such as reflective practice, after school services and youth work in interdisciplinary teams. Dana has a BA in Psychology from SUNY at New Paltz and a Phd in Educational Psychology from CUNY Graduate Center. She also runs the facebook group Advancing Youth Work: Current Trends, Critical Questions.

So Dana, what will youth work look like in 2013???

Dana Fusco, Professor, City University of New York, York College, United States

In the United States, youth work is not a unified or singular practice; rather, it has been described, and still is, a family of practices (Baizerman, 1996[1]). That family provides, in the most ideal circumstance, a plethora of diverse opportunities for young people. What we, as youthwork practitioners hope is that the set of diverse experiences known as ‘youth work’ will help young people to live rich, healthy, and fulfilling lives now and into the future. Our praxis is grounded or contextualized in the actual, not theoretical, lives of young people; is responsive to their lived experiences, their hopes, their aspirations and dreams; and proclaims a participatory and democratic approach that supports youth voice and agency as a part of community engagement.

In the places where youth work looks like this in 2012, I suspect it will continue to do so in 2013. That said, there are some trends on the horizon that potentially put the family of youth work practices in jeopardy. If we think of youth work as a stew, then each practice is an important ingredient towards a ‘tasty’ and healthful creation. In the U.S., our stew seems a bit ‘soupy’ these days, with ‘critical’ and emancipatory forms of youth work being those most often removed or replaced. This trend was precipitated by several sociopolitical and economic factors, with the most direct consequence being the pressure for out-of-school, nonformal environments to link up to, connect with, and supplement school. The goal for those who hope to formalize out-of-school environment is that there is a collective impact towards meeting NCLB (No Child Left Behind) targets (standardized test scores in reading and math).

The trend of youth work moving towards formalized education began with the development of a billion dollar federal reserve for afterschool programs under the Clinton administration, known as 21st Century Community Learning grants. These grants had two contradictory consequences. On the one hand, they put into the public eye, the importance of afterschool environments, many of which at that time were the youth-club-in-community-center variety, and legitimized these spaces as critical for young people. On the flip side, those dollars came with “strings” to improve academic outcomes. Some community agencies with a strong history of local work with young people have maneuvered within the structure to work in participatory and emergent ways. Many have closed their doors. Those newer to the scene might be doing good educational and ‘youth development’ stuff after school, i.e., enrichment and project-based learning, but not youth work in the way we have known it.

This situation leaves us with two potential possibilities for the future of the field. First, we can name these afterschool practices as part of the family of youth work practice and accept them as such. Second, we can decide that this form of afterschool, which is geared towards ‘a priori’ academic outcomes, might be too predetermined and ritualistic to be considered youth work at all. If this is the case, we must not only define youth work by what it is not but by what it is – an emergent and relational form of workingwith young people that is community-based, participatory and responsive, or what I am now calling, critical youth work (CYW).

If we choose the second option it will be critical that we more clearly define the purpose and values of CYW. As I see it, CYW aims to co-create spaces with young people where they can lead and learn. In this formulation, youth work begins with young people’s concerns, interests, goals, and/or needs, and positions practitioners to construct a ‘use of self’ that creates a relational web of possibility. Then, in this conception of the future, it is the education of the youth worker that becomes increasingly pivotal.

In 2013, it is not only changes in youth work practice that we must attend to but also changes in youthworkeducation (YoEd) In the U.S. we have seen an explosion in YoEd within higher education, a 900% increase over the past four years with most of these framed as ‘youth development.’ Conversely, in the U.K. and Australia, longstanding youth work courses and degree programs have closed their doors including those found at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in Australia, University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, and Manchester University. While the reasons for such closures have been couched in economic and enrollment terms, one wonders why Youth Work/Youth Studies then and not Latin or philosophy, which equally might enroll under five students each year. The lack of understanding among higher education administration about community-based youth work is partly to blame. The title itself, youth work, leans towards the vocational, not the liberal arts. In 2013, it is hard to predict where those who want to study youth work and youth studies in these countries will go. If they go into existing, related disciplines, e.g., social work, then youth work will too likely become case management; if they go into education, then youth work will become para-teaching. With such potential outcomes, an international community of youth workers and youth work educators is needed whether in the form of an association or something else in order to work towards saving/reclaiming and re-thinking the discipline of youth work. I believe today it is in our international community that we have collective power and bargaining to legitimize the work and the body of knowledge that we have co-created as a viable area of study and practice for working with young people.

In 2013, this would be something to aim for!

[1] Baizerman M. (1996). Youth work on the street. Community’s moral compact with its young people. Childhood, 3, 157-165.

For more than 20 years, Dana Fusco’s research has focused on youth work as a practice and a profession and has led to increased national and international recognition. Recently she was the keynote speaker at the History of Youth Work conference in Minnesota and presented at the International Conference on Youth Work and Youth Studies in Glasgow. She serves on a national panel of leaders in youth work, the Next Generation Coalition, has authored dozens of peer-reviewed articles and produced the documentary, “When School Is Not Enough.” Professor in Teacher Education at York College, CUNY, She received her Ph.D. in Education Psychology from the CUNY Graduate Center.

Dana is The Editor of the path-breaking book Advancing Youth Work: Current Trends, Critical Questions, which brings together an international list of contributors to collectively articulate a vision for the field of youth work. This book is a must have and is one we would recommend you all get. We did. You can buy it here.

What will youth work look like in 2013???

Today it is my pleasure to kick off a series that will take us to mid January 2013. In this series we will hear from some of the leading minds in youth work from throughout the world as they answer the question, “What will youth work look like in 2013???”

Today’s Guest Post is written by one of our favourite your work blogging duo’s, Shae and Stephen Pepper. In their short time on the scene they have rocketed to the front page of Google with their amazing blog posts on everything from ‘games for youth groups’ to ‘how to run a retreat’ (check out their amazing book). They have also been our biggest supporters in the blogosphere by promoting us in their weekly top blog posts of the week.

So guys, what will youth work look like in 2013???

University

Over the last 25 years, the cost of university education in the US has more than tripled, which has resulted in 1 in 11 people defaulting on their student loan repayments within two years of making payments.

The Minerva Project is seeking to be a virtual Harvard, while charging tuition fees that are less than half the price of regular universities. Udacity is offering higher education for free. Khan Academy has delivered more than 200 million free lessons online. Codecademyis teaching people how to code for free.

-

They’re unable to gain skills

- It’s harder for young people to get a job longer term

- The impact on their self-worth

- The decrease in social mobility

- Long-term societal issues

What does this mean for youth work?

-

Young people from low income households may have a hard time focusing at school simply because they’re hungry

- For churches, youth who were abused by their Dad will have a hard time relating to God as their Father

- Depressed young people can have physical symptoms, whether that manifests itself through illness or self-harm

What does this mean for youth work?

This post was written by Stephen & Shae Pepper of Youth Workin’ It. They blog about youth work 6 days a week and also offer consultancy, services and youth work resources for youth workers and organizations worldwide.

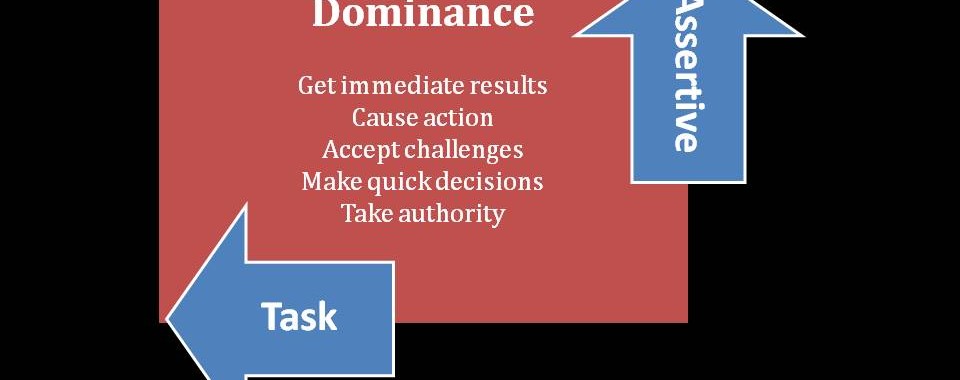

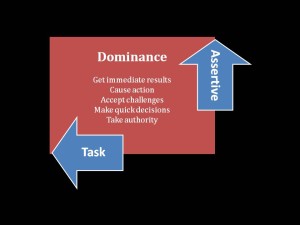

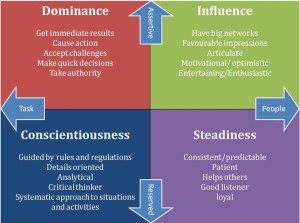

Observe the D in DISC for youth worker’s

Here are our top seven tips for working with people with DOMINANCE behaviour traits:

-

Communicate briefly and as to the point as you can. If you are writing an email and its more than four sentences kill it or cut it down. If you call them and it lasts much more than a minute they will start to wrap it up. If you are chatting with them… Ha Ha I made a funny. They would never chat.

-

Respect their need for independence. Do not impose upon them unnecessarily. Use your role power sparingly if you have it and if you don’t have any then only stand up against them when it is absolutely required.

-

Be clear about rules and expectations. Whether in a team meeting or a group be clear about what is and is not allowed. Be unmistakable about the outcomes expected and how to achieve them.

-

Let them take the lead. They usually have innate leadership ability so where possible let them have it. They will probably try to take it anyway.

-

Show your competence. High D’s respect clarity and results. If you stuff around and then do not achieve you are painting a sign on your back. Do your tasks, lead the group whatever you do; do it to the best of your ability.

-

Stick to the topic. One thought at a time and if possible no sub points. Do not go off on tangents and for the love of God do not do a Grandpa Simpson.

-

Show independence. Stand up for what you believe and do not be afraid to express your opinion. Be more forceful. You will think you are arguing. They will think that they are finally having a worthy conversation.

Here are just a few people you might have seen on a tv that have DOMINANCE in their behavioural style.

Youth Justice: Restoration or Retribution?

(A sample of the young boys handy work… It could hold over 1000 people.)

“Youth workers are facilitators of restoration not social controllers.”

If you take on the challenge to provide a restorative environment for young offenders then you may find yourself having to become a canny outlaw. It is hard to fight for whats right in the face of the easy way of following the rules. Our young people need you to speak for them. They need your actions and support. They need you to be practically wise. They need restoration.

For more info on restorative justice see Howard Zehr below.

What are your thoughts???

Leave us a comment below or post a comment on facebook and twitter.

Accountability

If you have any questions drop us an email or chat to us on facebook and twitter.

Reflective practice: Why we should journal.

Reflective practice is by no means a new idea in the field but it is one that is not widely implemented. Reasons for this are wide and varied but are mostly end up being because people do not know how to do it or what it would look like. In university courses there is often discussion about being critically reflective and aware of your work however when a student becomes a staff member the critical thinking is left behind an ever growing wall of bureaucracy and paperwork. This often leads to frustration on the part of the staff member and in more extreme cases a complete break down in effective service delivery.

When I was a young youth worker I completed an internship with a small organisation that trained youth workers to work in schools. One of the most interesting aspects of the internship (and the one I most struggled with) was a forced weekly journalling session. Some of my best reflections on where I was at as a youth worker, what I needed to work on and how I practiced came during this time. However, I struggled with the exercise because I was not given a reason to do it. I struggled because I was not given a format or template to do it. But most of all I struggled because critical reflection was not something that had been instilled in me as a youth worker either in practice or study.

- To deepen the quality of learning, in the form of critical thinking or developing a questioning attitude

- To enable learners to understand their own learning process

- To increase active involvement in learning and personal ownership of learning

- To enhance professional practice or the professional self in practice

- To enhance the personal valuing of the self towards self-empowerment

- To enhance creativity by making better use of intuitive understanding

- To free-up writing and the representation of learning

- To provide an alternative ‘voice’ for those not good at expressing themselves

- To foster reflective and creative interaction in a group

Journaling provides a great base for the individual worker to begin to develop their reflective practice. Here is one template i have come accross that has worked over the years to help me reflect on my practice.

- Identify and describe the experience/issue/ decision/incident

-

Identify your strengths as a practitioner

-

Identify your feelings thoughts; values, feelings and thoughts of others involved

-

Identify external and internal factors; including structural/oppressive factors etc

-

Identify factors you have influence or control over and those you don’t ( do others?)

- Identify knowledge used:

- factual

- theoretical

- practice

-

Develop an action plan: what do I need to do first, second and third and so on

Let us know how you go on facebook and twitter.

References

Let us know how you go on facebook and twitter.

What extra standing will i have if Youth Workers professionalise?

Why do I think this you may ask??? Basically because anyone can call themselves a social worker and there is nothing that they can do about it. For all intents and purposes the AASW is a registration board for all those social workers who want to be members. there is no requirement of them to be members and no legislative power to make it a requirement.

The difference in a professional association such as the APS, the Victorian Institute of Teachers or the Nurses Board of Victoria is that they are legislated and mandated by the Government and as such are able to “register” and “qualify” their membership. You cannot call yourself a Psychologist, Teacher or Registered Nurse if you are not one, and you can be held accountable by the law if you do so without their authority. It also means that you can be removed from practice if you are deemed to have broken the rules of the association.

If Youth Workers are to reach the level of PROFESSIONALS we need to take our campaign to the next level. Social workers are starting to move this way through the provision of Medicare provider numbers to those in their membership who qualify, however even this needs to go a step further. Members must be required to register with the association to practice.

This is the same for Youth Work. At the present anyone can call themselves a Youth Worker. Some of my best mates and closest colleagues are unqualified Youth Workers, however if we are to become a body of professional workers then we need to be required to register.

The only way a person can be required to register before practice is if they are legislated to do so. You don’t often see people practicing as a doctor without registration for long before they are caught and arrested. The same should be said for Youth Workers and Social Workers.

We need to advocate for this intervention if we are ever to be taken seriously as a profession. What extra standing will I have if Youth Workers professionalise? Little if any, because at the moment the current form of association in Victoria will render us little more than a club.